Split Personality

The Ugly Side of Half Marathons

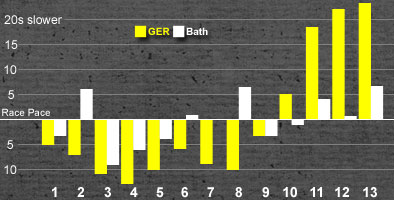

I've raced two half marathons in the last twelve months, and had two very different experiences. At the Great Eastern Run, I rattled out nine consecutive eight-minute miles, then experienced the bodily equivalent of that light on your dashboard that means you'll soon be driving a hire car. In the second race (Bath Half) I ran the same sort of pace overall, but managed to hold on to things for the whole race. This graph shows my average speed as the miles progressed - can you see when I called the RAC?

Getting your endurance training and race pacing licked is an essential skill, and getting it wrong can ruin your day. Running well doesn't just involve running fast - it's about learning how to run consistently and finish strongly - and that's something we can all work on, no matter what speed we're capable of. Watch any televised running, and you'll see the splits of the leading athletes pop up as they glide along - they're remarkably consistent. When Paula Radcliffe set her record marathon time, her fastest mile was 4:57, and the slowest was 5:18. And when Patrick Makau set the men's record, his fastest and slowest 5k splits were just 39 seconds apart.

There are thousands of half marathon performances in the Fetch database, and some interesting trends that we can all attempt to overcome.

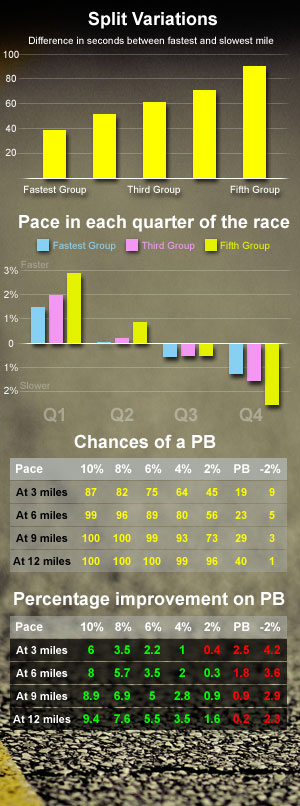

Let's warm up by looking at the variation between the fastest and slowest mile of our runners - see the first graph on the right. The fastest group (the fastest thousand runners) typically squeeze all their half marathon mile splits within a 39 second margin. The slowest thousand runners typically show a variation of 89 seconds between fastest and slowest mile. Improving consistency is one sign of good training, but it also comes from a good race strategy.

How does it work? Do the faster runners start more conservatively? Do slower runners blow it all in the first mile and then spend the next 12 paying the price? The next graph shows how each of our groups handle pace in each quarter of the race. It seems that even the fastest group can't resist the urge to go off quickly, typically 1.62% faster than the pace they achieve overall, but it's our slowest group that find it hardest to curb their enthusiasm, running the first three miles nearly 3% faster than overall race pace. In the second quarter, reality bites all round; and in the third quarter, the emphasis switches to holding on. By the last three miles of the race, all groups are struggling to hold on to the initial pace. But whilst our fastest group are 1.25% slower than their overall pace, our slowest group are swearing like wounded pirates, paying back the loan at a stiff 2.5%.

Lots of us are driven by the urge to beat our best times, and it's hard not to let adrenaline take early control on the big day. I wondered if it was something that comes with experience, but even amongst runners with five, ten and even twenty half marathons in the locker, 80% of people run the first three miles faster than they run the rest of the race.

So it's pretty difficult to keep yourself under control early on, and every likelihood that you'll slow down as the race goes on. Getting the balance right is the key to a PB and a smile at the end.

The first table on the right illustrates how your PB dreams are linked to how far ahead of the game you are throughout the race. For example, if you get to six miles, and your overall pace 4% faster than your PB pace, you've got an 80% chance of holding on for a PB - but if you're only matching PB pace, you've only got a 23% chance.

It's tempting to run your finger along the rows and draw the assumption that if you go bananas in the first three miles, you've got a great chance of getting a PB. If you need me to point out the flaw in that thinking, then you may as well go the whole hog and run the whole race in a pair of cut-off jeans and some flip-flops. These figures are based on an analysis of runners who are (for the most part) training sensibly. Without adequate long run training and preparation to handle race pace, you're in for a lot of pain.

Overall though, building up a buffer at the start of the race does increase your chances of getting a PB. Too much, and you can spend the rest of the race managing a drastic slowdown, feeling dreadful, and being eyed eagerly by the folks from St Johns. But those who take a conservative approach to undercutting their PB pace end up slowing down as a half marathon wears on, and what might feel like a comfortable-if-small PB in the first six miles can gradually slip away.

The final table shows how your race outcome is linked to your progress at various points in the race. For example, if you're running at exactly PB pace when you've completed six miles, the bad news is that you're likely to miss out on a PB by about 1.8%. However, if you're just 2% faster than PB pace at the six mile mark, you're on target to take a princely 0.3% off your best time!

I will end with the usual cover-all caveat - if everyone was the same, we wouldn't need averages - and that's all these are. But take a second look at your race pacing, and you might find the key to your next PB.

*EDIT* I'd like to make it clear for anyone reading, that I really don't advocate going out like a nutter, then trying to hold on. The fastest group in my study were most conservative when setting their early pace, and consequently, they stayed in control towards the end of the race. Rave safe kids.

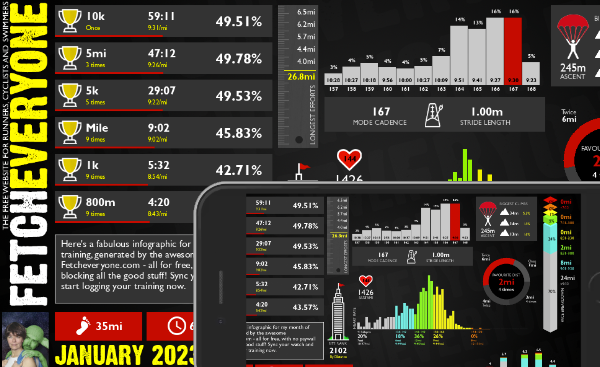

Monthly Summary

A brand new shareable infographic showing a colourful breakdown of your training month.

Marathon Prediction

We delve deeper to give you greater insights when working out your goal marathon time.

Pre-race Training Analysis

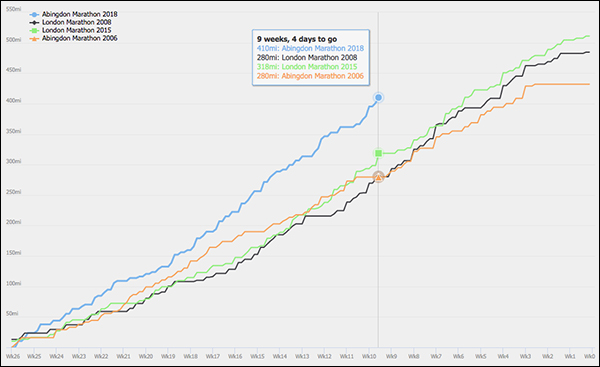

See your accumulated mileage in the weeks leading up to any event in your portfolio, and compare it to your other performances

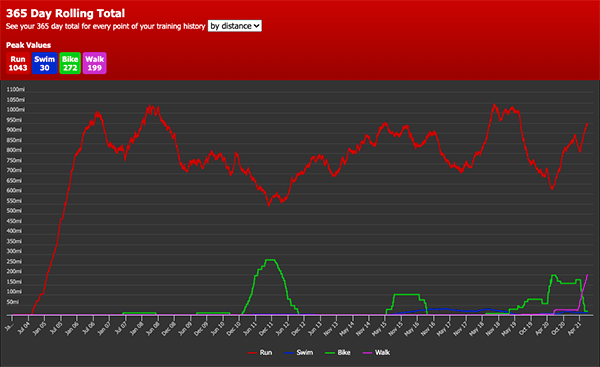

Your 365 Day Totals

Peaks and troughs in training aren't easy to find. Unless you use this graph. Find out what your peak training volume really is

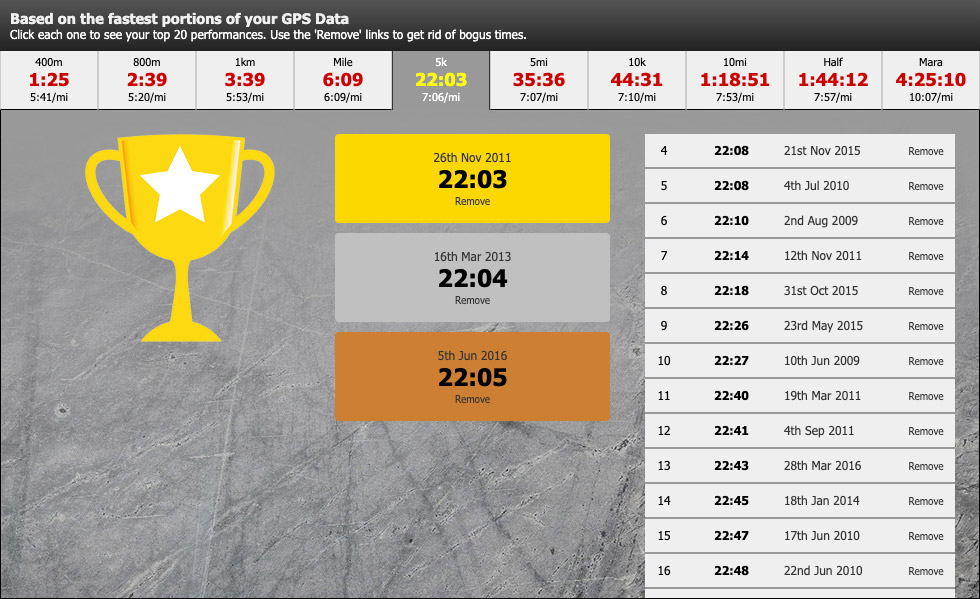

Benchmarks

See the fastest portions from all your training runs. Filter by time to give you recent bests to aim at. Every distance from 400m to marathon.

Fetch Everyone Running Club

Join our UKA-affiliated club for event discounts, London Marathon ballot places, the chance to get funded for coaching qualifications, and a warm feeling inside.

Leave a comment...

-

I will have to read this again when I have more time. Curently I could only vote Confused which isn't on the list

snogard

-

Wonderous use of the mountain of data at your disposal these days.

paul the builder

-

I was referring to the fact that 80% of runners slow down during half marathons irrespective of whether they start off above or below their PB pace. So it follows logically that you need that buffer.

fetcheveryone

-

Extremely interesting. I started reading sure that negative splits were going to be the prescribed order of the day but no. I'm not sure such an extensive set of data has been used to analyse the theory before? I would guess not especially with on the whole average runners (sorry but most of us are aren't we?) Have you ever thought of writing a book Fetch you may completely turn the prescribed science of racing and training on its head and all with scientific theory to back it up.

MaT.T

-

Brilliant piece to share! I when first started running would go off like a bullet and pay for it but now I have learned to be more conservative about my racing. Sometimes if there's someone in front and you want to or have to reel them in then it's time to dig into the reserve early doors but make sure there is still enough in the tank for the latter stages so one isn't running on vapor!!

Sunbed Athlete

-

Do 80% slow during half marathons due to lack of endurance training?

jasond

-

can't we?

MaT.T

-

I love this type of geekery. Or is it nerdery? I never can tell. Either way I love it. Now all I've got to do is apply the learning.

Nellers

-

The top 1000 are sub-1:28:33. FYI the top 100 are 1:17 and below - and they follow the same trend - 79% of them do a positive split 85% of them run the first three miles faster than race pace.

fetcheveryone

-

Cracking article which flies in the face of all that I have been coaching my clinets (succesfully) in. I think the key here could well be what the Terminator says - that the majority of us don't train particularly effectively for longer distances. I used to start too fast and hang on and got great PB's that way. But as I've got faster / fitter I've started gaining PB's by starting slower than race pace and building up to finishing faster than it. However that is how I have been training. So I guess you get what you train for. When most of us train we do train faster at the start of a run.

Lumsdoni

-

Fetch just as a thought can you analyse the stats on the 20% of the runners who speed up during a half marathon? How does their PB success rate compare to the other 80%?

Lumsdoni

-

Lums - I'll get back to you on that. Out of 7836 samples 1786 were negative splits and 43% of those resulted in PB's. On the flipside 6026 were positive splits and 36% of them results in PB's. I know I'd rather have an experience like I did in Bath where I kept a lid on my pace and finished well - rather than GER where I set off all ballsy and came home in limp mode.

fetcheveryone

-

Have sent you a feedback on this. I feel that the data or analysis is giving a skewed picture somehow as going out hard doesn't usually lead to best performance - 'even pacing' usually gets best results. However I may have misread or misunderstood the message somehow. I'll wait for your response to feedback. Cheers :-)G

HappyG(rrr)

-

Have sent you a feedback on this. I feel that the data or analysis is giving a skewed picture somehow as going out hard doesn't usually lead to best performance - 'even pacing' usually gets best results. However I may have misread or misunderstood the message somehow. I'll wait for your response to feedback. Cheers :-)G

HappyG(rrr)

-

Intriguing - on the back on only one Half I set out very conservatively and ran a negative split (62.30mins first half 59.50 mins second) which I was quite proud of - and it certainly helped me enjoy the whole experience a great deal more. Having for years run 10ks with a 'build-up a buffer & hold on theory' that failed dismally to secure a PB I was very determined not to do that with the Half. I try and run most of my long runs progressively.

Autumnleaves

-

Great article. Nice to see something based on a sample of ordinary runners.

leaguefreak

-

Superb article well done. Only recommendation has been mentioned by PtB first bar should be in percentiles as well. A 10% variation for a 6min/mile person is 36 seconds while for a 9min/mile 54 seconds so it does make sense that the faster runners will have smaller variation in absolute time for their splits.

minutehunter

-

HappyG - I'm not sure I can say it any clearer - I don't advocate starting off like a nutcase. The data does show that 4 out of 5 runners slow down and the example I pick from the table shows that if you aim for just 2% faster than PB pace by the six mile mark you're inside PB territory. For an eight minute miler that's suggesting you get to mile six at 7:50 pace.

fetcheveryone

-

Ok. I am going to try this. My HM PB is 1:39:09 I make that I should be 119 seconds up (4%) at the halfway point then I have an 80% chance of a PB. That as they say is a plan. I don't run a HM until October for one reason or another but I may even practice this over 10k some similar rule is probably in all you data for 10ks too.

Ocelot Spleens

-

Fantastic article. Confidence intervals (no pun intended) would put the nerdy icing on the cake!

Janiew

-

Great article. I'm certainly in the burn it up in the 1st 3 miles camp. I know it's wrong but it's been successful ( in my own slow way).

PeterG

-

This is an extremely intersting article but I feel the 'Chances of a PB' table could be massively mis-interpreted. This is because I feel it is likely to be largely measuring genuine improvements by runners rather than improvements due to 'race pace strategy' so perhaps a measure against the runners current highest WAVA rather than a PB for h/m would show different results. The other concern I have is that I am more tempted to log my splits in the training database if I've had a 'good' race that does not necessarily mean a PB but more probably if I have finished strongly (and so felt reasionably happy about the race) - so perhaps there is some self selection in the stats you are using.

Heavyweight

-

This is very interesting. It would also be interesting to see a graph showing chance of a PB plotted against the % difference in pace between first half and second half of the race plotted separately for the fastest third middle third and slowest third of runners. I will stick my neck out and predict that despite the evidence that even most of the fast runners tend to slow down the greatest chance of a PB for the fastest third would be with even pace or a small negative split. However perhaps most interesting is what strategy worked best for the slowest third.

Canute

-

Lovely stuff - thanks. Nevermind PBs the greatest pleasure of starting slowly and keeping something back is overtaking people towards the end.

Festina Lente

-

Is there any way of saving this information in to a word file. I have seen some really interesting articles previously and have wanted to look back at them and now I can't find them. It would be really useful to save the articles that I know I will want to look back on like this one and the previous article.

ICanDoThis

-

This seems like there might be some observer bias. If you set off at your perfect pace ran the first ten miles exactly to plan but then ran out of energy / pulled a muscle realised that your cold wasn't quite gone etc so you slowed downin each of the remaining miles it would LOOK like you had set off too fast (first miles much faster than average). So of course everyone who was slow in the final miles ran the early miles too fast - because the slow final mailes will skew the average - but did they really run them faster than they had planned to or did they get carried away and abandon their plan? I'd be interested to know that and naybe the data can show what pace they were training for?

Unicorn

-

When I was younger I expected to run 5:20 first mile aiming for a 75-76 half. Yes it was too quick but I always enjoyed plenty of room from early on.

Muds

-

TT- sorry I missed your question! Yes I tend to slow in the latter stages but can often pick it up again in the final mile. Just checked my PB splits from last year which back this up- although last mile was downhill

Splits were: 5:49 6:05 5:59 5:59 6:07 6:08 6:05 6:09 6:10 6:05 6:11 6:11 5:41 45. Saying that still pretty consistent - the first mile was uphill though and TOO FAST!

Splits were: 5:49 6:05 5:59 5:59 6:07 6:08 6:05 6:09 6:10 6:05 6:11 6:11 5:41 45. Saying that still pretty consistent - the first mile was uphill though and TOO FAST!

jasond

-

Previous performance isn't an indicator of future results. This is saying that 80% of people who were 4% up on their PB pace at 6 miles managed to get a PB. That doesn't mean that 80% of people who are 4% up at 6 miles will get a PB in future - it does indicate that a group of people with a similar perspective as people who have ran before this statistic was generated should get similar results.

DaveG

-

An interesting read there...

Gooner

-

I certainly feel it is more mental than anything else with my running. If I am going well in the first 4-5 miles and have a small buffer I feel that I can slow down any time I want if I need to to have a bit of a recovery period while racing which typically means that I don't! If I am struggling to get to my PB time in those first few miles I end up in negative mental territory and so it is all downhill so to speak from there. Maybe I just need to HTFU

CStar

-

What I'm trying to figure out is how this relates to target pace.

angryjames

To comment, you need to sign in or sign up!One minor thing - I think the first bar graph would have been best expressed in % just as the second is (although that may have diluted the message somewhat...)

And one major thing - 'Overall though building up a buffer at the start of the race does increase your chances of getting a PB'. I don't see any evidence for this here. There's nothing to say that 'buffer then slowdown' ends up with a faster result than even pace. Given that most people are following the 'buffer then slowdown' strategy then of course the data will show that starting faster finishing faster. But there's no way I can think of to analyse the 2 alternative strategies (unless you have a follow-up article planned...:-))

TT- most of us can't be average

If it is down to lack of endurance training are we saying only 20% train properly. What is your experience of half marathons JD? How many races of half marathon distance or further have you managed negative splits? Genuinely interested....

How does the size of PB's gained compare to the 80% and of those runners who do speed up is there a trend in where they sit in the overall speed spectrum? ie - are negative split runners predominantly faster or slower runners?

As for the buffer if you ran a HM on a given heart rate your pace would probably follow a similar pattern as the buffer graph so as the majority runs to feel I think it makes sense.

I guess it comes down to confidence in your numbers experience and doing the right things in training. Currently I'm in a low mileage mode and happy to experiment even write off a race or two as I build up again.

Note to self - slower is good keep repeating till it sticks

If you ignore what these statistics are saying you should see similar results. But once you change your behaviour to try to obtain these results you are at danger of going off too fast and fading rather than running at the pace you're comfortable with and achieving a fast time as a result.

This is why the results don't surprise me. I'd imagine must people who are 4% up at 6 miles to be in stronger form than when they set their PB and therefore it's the improvement in form which produces the time not the increased pace which produces the improvement.

If people generally run a positive split many people will be up on their PB overall pace but get to 6 miles slower than then did in their PB race. This could lead people to falsely believe they were faster but faded when actually they were behind the splits from their PB throughout. That's something I've never really considered before when I'm trying to assess how I'm doing in races - perhaps thinking about my time at 3 6 and 9 miles during my PB would be more sensible than just multiplying my average minutes per mile pace by the number of miles.

Say you train consistently for a 8:00 mile and then on race day you fall prey to overexuberance and storm off at 7:30 for the first three miles. Are you going to end up losing that 90 second gap that you built up in the first three miles because you hit the wall so hard later on that you fall to bits or is it going to be an adequate cushion. Just because we see here that people *did* improve we don't know that they wouldn't have improved more if they'd not gone out as fast as they did.

Like Wirral Dave says it could just be they have stronger form and they're getting better at applying a flawed strategy: suppose you PB'd with a positive split went off and trained and took 3 minutes out of your PB the next time you ran a positive split. I'm not sure this data can tell us whether changing to a negative split would have been superior or not.